How the sunk cost fallacy is ruining your life and you don't even know it

How to make intentional decisions and prevent long-term mistakes

If you’ve studied any entry-level economics class, you’ve probably heard of sunk costs or the Sunk Cost Fallacy.

If you can’t remember how your boring Econ 101 professor described it, here’s a good summary from The Decision Lab:

The Sunk Cost Fallacy describes our tendency to follow through on an endeavor if we have already invested time, effort, or money into it, whether or not the current costs outweigh the benefits.

There are many examples of this that may occur in your day-to-day life.

Finishing a movie because you’re 30 minutes in even though it’s been awful and disrespects its source material (yes Uncharted I’m looking at you).

Eating the last 3 slices of last night’s pizza even though you know it might make you feel sick because you need to get your “money’s worth”.

These are two small examples, but if you extrapolate these decision-making mistakes to the larger life-impacting decisions, you may have a problem…

Frm: Ambition & Balance by Doist (great newsletter/blog by the way)

Why is this important?

We tend to think of ourselves as rational thinkers. We like to think that we make the best decisions for both our present and future selves.

But the fact of the matter is that we are actually very emotional beings, we tend to make decisions with incomplete information, and we are naturally subject to loss aversion.

We are in fact…. irrational.

As mentioned earlier, sunk cost fallacy often impacts even our smallest decisions. If it impacts these small decisions, then it definitely at least somewhat impacts our very important, large decisions.

An Extreme Example

An example I’ve thought of lately is applying this to present-day career decisions.

Have you ever taken the second to realize that the job/career you’re pursuing — has come downstream from a decision that you made when you were 17 years old?

Which decision you may ask?

The decision on what to do after you graduate from high school.

Whether that decision led you to go into a certain university program, start a business or go into the trades, this is a decision that undoubtedly has a large impact on the beginning of our young careers.

However — this is a decision that we make before our brain is even fully developed!

From the University of Rochester:

The rational part of a teen’s brain isn’t fully developed and won’t be until age 25 or so.

Adults think with the prefrontal cortex, the brain’s rational part. This is the part of the brain that responds to situations with good judgment and an awareness of long-term consequences.

Teens process information with the amygdala. This is the emotional part.

Those who go to school for accounting usually end up working in accounting.

Those who go to school for engineering usually end up working as engineers.

Those who go to school for architecture usually end up becoming architects.

Which I guess makes sense….

But it’s just scary that we made this decision when we were so young and use that decision as the basis to decide which career to potentially spend the rest of our lives in.

The moral of the story is to question the prior decisions you’ve made. The decision you made 5 years ago may not be in line with the person you are in the present.

Re-analyze that decision, and make sure that the decision you are making today is with present-day you in mind.

Just because you’ve spent 5 years doing something, doesn’t necessarily mean it’s the right thing for you to do.

Abstract Point

Maybe we as humans need more time for exploration when we’re young.

Why is it that there’s so much pressure to start our individual careers at such a young age?

Why is it considered not normal/weird to be a mature student studying their undergrad at university?

Why is it sometimes frowned upon for individuals to take time away from the traditional path before starting their corporate career paths?

Just some thoughts…

How to Beat Sunk Cost Fallacy

Side ramble about the meaning of life and society aside… How can we beat sunk cost fallacy and ensure that we are making the most optimal decisions for the current version of ourselves?

Decide don’t Slide

Take Time and Map it Out!

Do a Quarterly Decision Audit

1. Decide don’t Slide

How to Not Die Alone by Logan Ury is a fantastic book about modern dating and relationships but I think one of the best lessons from the novel is the importance of intentional decision-making.

Ury refers to this process as “deciding not sliding”. She says that when approaching important relationship decisions, often people slide into making these decisions.

From the book:

Deciding means making intentional choices about relationship transitions, like becoming exclusive or having children.

Sliding entails slipping into the next stage without giving it much thought.

She then includes some studies to discuss the difference:

Researchers at the University of Virginia found that couples who made a conscious choice (deciding) to advance to the next stage of their relationship enjoyed higher-quality marriages than those who slid into the next stage.

Researchers from University of Louisville and the University of Denver found that individuals who tend to “slide” through relationship milestones feel less dedicated to their partners and engage in more extramarital affairs.

The findings suggest sliding through decision points can put a relationship at risk.

Relationship decisions where couples slide instead of deciding could be:

When making that next step to make the relationship official

To introduce them to your family

To move in together

However are you as a couple doing these things because it’s the right decision for both of you, or are you doing it because it “just makes sense” or “it feels like the right time”?

Everyone else is doing this at our age, so why don’t we?

Ury instead says that when it comes to making these big changes, we have to acknowledge them as important decision points.

As such, you need to take this important decision point as a time to pause, take a breath, and reflect. Shift your brain from a mode of unconscious thinking to deliberate decision-making.

2. Take Time & Map it Out

When you’re in the process of making an intentional decision instead of sliding for anything that will have a material impact on your life — remember to take your time to map out the decision.

If it’s a material decision on either a financial or time basis — realize that you must invest the necessary time in order to make this decision.

What do I mean by this?

Spend a few quiet hours to actually map out your thoughts about this decision.

Do a risk-benefit analysis, do a fear planning exercise, or write a pros and cons list.

Shane Parrish has a great decision-making framework that he uses called a decision journal, which I’ve been trying to adapt into my day-to-day. In this decision journal, you write out the potential outcomes, the problem you’re trying to solve, and many other variables that may impact the success or outcome of the decision.

This process plots out the entire decision-making process, giving you a strong idea of where this decision may take you and if you’ve calibrated it enough.

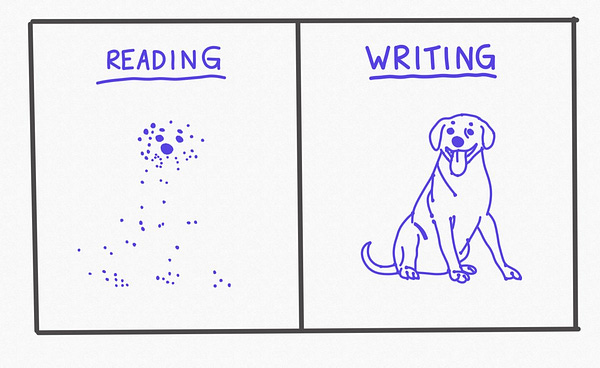

Overall — writing is the form of thinking that will clear your mind and the decision-making process. As David Perell illustrates in the photo below, writing can help you connect the dots from your thoughts to ensure you’re making the right decision.

3. Do a Quarterly Decision Audit

As we’ve just completed the first quarter of 2022 (crazy right?!), I’ve thought more and more about the reflection I want to do throughout the year. It’s super critical to reflect on how we spend our time to ensure that we aren’t losing track of our yearly aspirations and tracking the progress of our systems.

In addition to overall reflection, I think the act of reviewing the large decisions you’ve made is a great way to improve your decision-making ability.

To again quote the awesome Shane Parrish, he says that “we are, in so many ways, the product of our decisions.”

Yet, how often do we spend the time to reflect on the trajectory of our past decisions? Often we don’t at all!

Making the decision is only one part of the equation. Making the decision gives us experience, but that doesn’t necessarily mean that we’re improving.

No one gives us feedback on our decisions. Not from our bosses, our partners, or ourselves (because of personal biases). Our feedback is almost always performance/end value-based.

Therefore, it’s really important to study how we make decisions.

Using the writing we’ve completed in Step 2, every quarter or every year, take the time to evaluate the results of the decisions you’ve made. See what has provided great success and your areas of improvement, and eventually, you’ll calibrate to what is best for you.

If you’ve made it this far, thank you for reading :)

This was one of the longest essays I’ve written since high school — but it was a lot of fun.

Please like and share this post if you enjoyed it!

PS. I didn’t actually watch Uncharted, but they didn’t cast Jeremy Renner as Nathan Drake so I’m sad :(

![The Sunk Cost Fallacy & Your Productivity [comic] - Doist Blog The Sunk Cost Fallacy & Your Productivity [comic] - Doist Blog](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!kvZO!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fbucketeer-e05bbc84-baa3-437e-9518-adb32be77984.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Fd8289a27-da9a-41e4-8e0f-dd5ad05084e0_1714x2126.png)